Effective grantmaking:

part two

This is the second part of a guide to effective grantmaking outlining best practices to improve processes in the award and post-award phases of philanthropy

This is the second part of a guide to effective grantmaking outlining best practices to improve processes in the award and post-award phases of philanthropy

This is the second installment of a two-part series on effective grantmaking for corporate philanthropy. It introduces three key principles and related best practices to improve processes in the award and post- award phases of grantmaking.

Corporate giving is a key contributor to achieving community, national, and global development targets. In the first installment of this two-part series, we outlined the case for instituting practices that maximise the impact of corporate philanthropy. We also focused on key principles and practices that yield the best results from the pre- award stages of the grantmaking process.

While the pre-award phase is ripe with opportunities to insitute effective practices that contribute to positive outcomes, the opportunity to maximise impact does not cease as soon as a grant is negotiated. The award and post-award phases offer plenty of opportunities to secure positive influence and generate meaningful outcomes.

As you move into these latter phases of grantmaking, it is important to remember that you’ve elected to work with a grantee because you recognise that they have far deeper expertise in the issues being addressed than your own organisation does. As such, your interactions with your grantee in the post-award phase should be governed by an overarching theme: funders should listen closely to what their grantees are saying about their work, and as a general rule, they should listen more than they speak.

This is not to suggest that funders have no say in how grant resources are deployed, but by listening intently, funders can avail of wider opportunities to benefit from the expertise of the organisations they hand-selected as partners. This listening establishes a dynamic that emphasizes the value placed on input from grantees. That dynamic facilitates the transparency and trust that is integral to successful outcomes. Perhaps most importantly, it also helps to identify, anticipate, and mitigate risks that erode impact and threaten programme success.

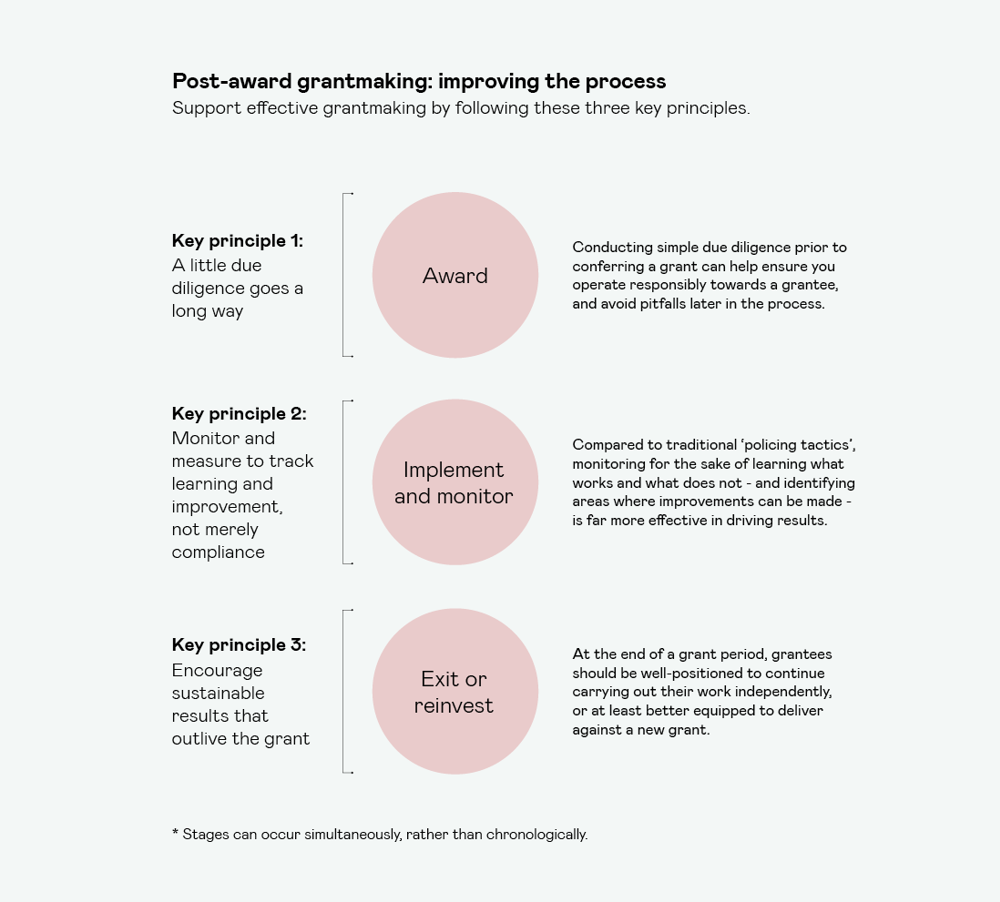

Funders can employ three key principles during the award and post-award grantmaking phases to strengthen overall outcomes. These are:

Why it is important. In the award stage, conducting simple due diligence prior to conferring a grant can help you operate responsibly towards a grantee and avoid common pitfalls down the road. One of the most important things to determine is whether your intended grantee can reasonably accommodate your grant within its existing structure, or at least has a sound realistic plan to do so with practical and sustainable growth.

Community organisations can cast a wide fundraising net and prioritise pitching for larger grants to offset the burdens of ongoing fundraising. These grants often call for innovative, scaled programming, and smaller organisations are under pressure to grow their staff, assets, and other infrastructure by orders of magnitude in order to deliver. Sometimes this growth is seen as an opportunity and can be achieved. More often than not, quickly and drastically increasing a grantee's operating budget or funding significant structural changes, is a risk that threatens the success of your grant and possibly the sustainability of the operations of the grantee. The risk is even greater if this is done based on funding from a sole grantmaker.

Best practice. While it is noble to support the growth of community organisations, this is best done incrementally over time and in conjunction with other funders. Responsible grantmakers should be aware of the ratio between the size of their financial grant and the total operating budget of their grantee. While there is no rule of thumb with respect to a ‘safe’ grant:size ratio, you should be reasonably assured that your grantee has the infrastructure, experience, and policies in place to effectively manage your funds, either in its current state, or by making reasonable adjustments.

If a grantee is planning significant growth based on a grant from a single funder, due diligence should be conducted to be determined if the grantee can continue to thrive should funding from that organisation stop. This can be carried out by reviewing audited financial statements, the current operating plan, anticipated funding pipeline reports and past performance reports, or by simply speaking with other funders who have previously worked with the grantee.

Your organisation plans to award a grant to a local NGO focused on educating children on eco-friendly habits. You and the grantee are both excited about the new programme and to align with the new school year, you bypass conducting any due diligence and rush to award the grant. Six months in, progress is slow and less than 20 percent of the target children have attended the events. Your grantee identifies human resource constraints as the root cause. The executive director confides that they’ve had difficulty hiring the 10 new staff members required to deliver the core programme activities. You are taken aback by the growth projection, as the organisation only had five full-time employees when you made the grant. Furthermore, it is based in a rural town with limited labour supply. It would be inconceivable for the organisation to double its staff in the course of a few weeks. Frustrated, you indicate that you are considering ending the grant due to non-compliance with performance measures. The director asks you to reconsider as a large portion of your grant has already been committed towards renting and outfitting larger office facilities to house the anticipated staff. Without your grant, the organisation would be unable to service its accounts payable and would likely have to shut down. You are left disappointed with the poor set of options before you and regret your decision to bypass conducting due diligence.

Why it is important. Tracking progress towards results is crucial during the implementation and monitoring stage. For grantmakers, monitoring often means ensuring that resources are being employed as agreed and that a programme is on track to meet a set of predefined targets. If progress is on track, the programme is believed to be in compliance with the terms of the grant.

While compliance is important, monitoring solely to ‘tick the boxes’ can be short sighted. Monitoring for the sake of learning what works and what does not, and for identifying areas where improvements can be made is far more effective in driving results. Approaching the monitoring function solely as a policing initiative drives a grantee to focus narrowly on reporting, while ignoring feedback loops and process improvements that can increase impact.

Best practice. To be useful, the process to monitor and evaluate should be adequately resourced, started as early as possible, and characterised as a learning exercise. Placing the emphasis on learning rather than ‘policing’ avoids the common ‘parent:child’ tensions between funders and grantees. It places grantee and funder on the same team and drives the focus towards solutions. Related best practices are listed below:

After the first year of a multi-year grant to reduce community reliance on single-use plastics, you eagerly await the year-end progress report. A few months earlier, you had carefully crafted the targets utilising international benchmarks as a guide. When your grantee presents the initial results and you are overjoyed to see that your grantee has outperformed the targets by as much as 75 percent in most areas. In your discussions, however, you learn that the programme actually had very little community participation and that recently passed local legislation restricting plastic bags in supermarkets probably accounted for most of the reduction in plastic use. Unfortunately, your targets were focused on consumer behaviour and were designed in a way that neither captured the influence of externalities, nor tracked programme attendance. You reflect on your target-setting exercise and regret that you did not invite the grantee to co-create those objectives. Had you done so, you might have been aware of the impending legislation and could have set the targets more appropriately – or even redirected efforts altogether.

Why it is important. Eventually, your organisation will have to decide to reinvest or move funding elsewhere. In the final stage of the grant process, it is responsible practice to ensure grantees are well-positioned to continue carrying out their work if a grant ends, or are at least equipped to deliver against a new grant. Due to lean budgets and heavy workloads, community organisations are rarely given an opportunity to upgrade their processes or develop their staff. The results achieved through your grant may not be longstanding without adequate attention paid to their sustainability and longevity.

Best practice. Community organisations generally only make operational requests they believe funders will accommodate. As a result, critical needs often go unfulfilled posing a risk to long-term results. Funders should be proactive in anticipating these capacity needs and offer support that helps ensure impact survives beyond the life of the grant. Other relevant best practices are listed below:

You are thrilled with the performance of a grantee that is working to conserve parklands and green spaces within your community. Your organisation is winding down environmental grants, and you are concerned about the sustainability of the project after your grant is complete. Sadly, there is very little awareness of the project, your organisation’s involvement in it, or the impact that has already been achieved. While your own organisation has a sizeable marketing department, you learn that your grantee has no staff dedicated to communications or social media. You regret not offering communications support through your internal capacity. The grant is almost finished, and without raising awareness, follow-on funding from other organisations is unlikely.

It's a good idea to use a strong password that you're not using elsewhere.

Remember password? Login here

Our content is free but you need to subscribe to unlock full access to our site.

Already subscribed? Login here